Low

-

Speed Of Life [2.45]

-

Breaking Glass [1.42]

-

What In The World [2.20]

-

Sound And Vision [3.00]

-

Be My Wife [2.55]

-

A New Career In A New Town [2.50]

-

Warszawa [6.17]

-

Art Decade [3.43]

-

Weeping Wall [3.25]

-

Subterraneans [5.37]

Bonus tracks on 1991 reissue:

-

Some Are [3.24]

-

All Saints [3.35]

-

Sound And Vision (Remixed Version 1991) [4.43]

Released:

-

RCA Victor PL 12030 - January 1977

-

RCA International INTS 5065 - June 1983

-

RCA International NL 83856 - March 1984

-

EMI EMD 1027 - August 1991

-

EMI 7243 5219070 - September 1999

Personnel:

-

David Bowie: Vocals, ARP, Tape Horn, Bass-Synthetic Strings, Saxophones, Cellos, Tape, Guitar, Pump Bass, Harmonica, Piano, Percussion, Chamberlain, Vibraphones, Xylophones, Ambient Sounds

-

Brian Eno: Splinter Mini-Moog, Report ARP, Rimmer EMI, Guitar Treatments, Chamberlain, Vocals on "Sound And Vision"

-

Carlos Alomar: Guitar

-

Dennis Davis: Percussion

-

Ricky Gardiner: Guitar

-

Eduard Meyer: Cellos on "Art Decade"

-

George Murray: Bass

-

Iggy Pop: Vocals on "What In The World"

-

Mary Visconti: Vocals on "Sound And Vision"

-

Roy Young: Piano, Farfisa Organ

-

Peter and Paul: Pianos and ARP on "Subterraneans"

Recorded:

-

Chateau d'Hérouville Studios, Pontoise/Hansa Studios, Berlin

Producers:

-

David Bowie, Tony Visconti

The genesis of Low, one of Bowie's most iconic and influential albums, lay in compositions originally intended for the soundtrack of The Man Who Fell To Earth. "We all had pressures, deadlines," recalled Nicolas Roeg in 1993. "Eventually we brought in John Phillips to do the score. Then six months later David sent me a copy of Low with a note that said, 'This is what I wanted to do for the soundtrack'. It would have been a wonderful score."

But Low was more than a rejected movie soundtrack: it was a form of creative therapy and one of Bowie's definitive changes in direction. Ravaged by cocaine and already fascinated by the avant-garde electronic music of German groups like Kraftwerk, Neu! and Tangerine Dream, David elected in the summer of 1976 to relocate to the Continent where, with the mutual support of the similarly afflicted Iggy Pop, creative rebirth would run parallel with physical recovery. "I was in a serious decline, emotionally and socially," he said in 1996. "I think I was very much on course to be just another rock casualty - in fact, I'm quite certain I wouldn't have survived the seventies if I'd carried on doing what I was doing. But I was lucky enough to know somewhere within me that I really was killing myself, and I had to do something drastic to pull myself out of that."

Although referred to ubiquitously as the first of Bowie's "Berlin" albums, the majority of Low was in fact recorded at the Chateau d'Hérouville near Paris, where Pin Ups had been made three years earlier and where Iggy Pop's The Idiot had just been completed. Although there was a certain amount of overlapping, the Low sessions proper began at the Chateau on September 1st 1976. Carlos Alomar, George Murray and Dennis Davis were recalled from Station To Station and were joined by keyboardist Roy Young, formerly of The Rebel Rousers. Bowie had initially hoped to secure the services of Neu! guitarist Klaus Dinger, but when the offer was declined ("in the most polite and diplomatic fashion," David later recalled), the job went instead to former Beggar's Opera guitarist Ricky Gardiner, who had originally been recommended by Tony Visconti to play on The Idiot (he didn't, but would subsequently work on Lust For Life). "He was totally left-field and completely savvy with special effects," Visconti later said of Gardiner. "I was in awe of him."

The most significant new arrival was Brian Eno, the erstwhile Roxy Music member whose remarkable solo albums had impressed David immensely. Roxy Music had supported several Bowie gigs in the summer of 1972, and the pair had met up again the following year when recording simultaneous solo projects (Diamond Dogs and Here Come The Warm Jets) at Olympic Studios. Acquaintance deepened into friendship after Bowie's Wembley shows in May 1976, as Eno recalled: "I went backstage and then we drove back to where he was living in Maida Vale. He said that he'd been listening to Discreet Music [Eno's November 1975 album], which was very interesting because at that time that was a very out-there record which was universally despised by the English pop press. He said he'd been playing it non-stop on his American tour, and naturally, flattery always endears you to someone." Likewise, Eno considered Station To Station "one of the great records of all time...I thought it was very strong, a real successful joining of that American urban funk scene with the kinds of things we had been doing in the early seventies."

Eno, with his neoclassical allegiances to minimalist composers like John Cage and Philip Glass, and his antipathy to every established convention of rock music, provided a stimulating contrast to Bowie. He has often stated that his ultimate aim is the subsumption of the individual, the effacement of the artist's personality from the music. By contrast, Bowie's work had hitherto thrived on the traditional dynamics of performed music and the fabrication of a succession of Ubermenschen to perform it. As Eno wrote many years later during the 1.Outside sessions, "I became the sculptor to David's tendency to paint. I keep trying to cut things back, strip them to something tense and taut, while he keeps throwing new colours on the canvas. It's a good duet."

Shortly before the Chateau d'Hérouville sessions Bowie contacted Eno and invited him to join him on what he explained would be a purely experimental album, originally to be called New Music: Night And Day. "What I think he was trying to do was to duck the momentum of a successful career," Eno later explained. His influence on the work that became Low would be difficult to exaggerate, but contrary to widespread belief he was not the album's producer. "It amazes me how so-called responsible journalists don't even bother to read the credits on the album," said Tony Visconti many years later. "Brian is a great musician and was very integral to the making of those three albums [Low, "Heroes" and Lodger]. But he was not the producer." Bowie has been equally keen to stress this fact: "Over the years not enough credit has gone to Tony Visconti on those particular albums," he said in 2000. "The actual sound and texture, the feel of everything from the drums to the way that my voice is recorded, is Tony Visconti."

Visconti, with whom David had last worked on Young Americans, had been called in to mix The Idiot and took the producer's chair for the Low sessions. He later explained that Bowie "wanted to make an album of music which was uncompromising and reflected the way he felt. He said he didn't care whether or not he had another hit record, and that [the recording would be] so out of the ordinary that it might never get released." Among the innovations Visconti brought to the studio was a new gadget called the Eventide Harmonizer which, as he explained to David, "fucks with the fabric of time!" The Harmonizer was the first machine capable of altering pitch while maintaining tempo, its influence most obvious in the speeded-up vocals on Bowie's later recording "Scream Like A Baby". It was this gadget that would engineer the drop in pitch on the tight, buzzing snare-drum sound that became one of Low's revolutionary characteristics.

Eno had already met David at his new home in Switzerland to discuss the project, but by the time he joined the Low sessions at the Chateau d'Hérouville the rest of the band had already begun laying down backing tracks. Significantly, Eno arrived direct from a stint working with the German supergroup Harmonia, who consisted of Neu! guitarist Michael Rother and the electronica pioneers Hans-Joachim Roedelius and Dieter Mobius of Cluster. The album they had just recorded with Eno would not be released until 20 years later as Tracks And Traces, but the influence of Harmonia on Eno's contribution to Low is beyond question.

Despite Bowie's unprecedented embrace of electronic processes, he was reluctant to use synthesizers merely to imitate other instruments: "I don't want to reproduce violin sounds - I'd much rather use the synthesizer as a texture," he revealed. "If I need a sound that I haven't heard in my head, then I require the assistance of a synthesizer to give me a texture that doesn't exist. If I want a guitar sound, I use a real guitar, but then I might mistreat it by putting it through the synthesizer afterwards and deforming the sound."

This approach was key to Bowie's methodology: as ever, he was less interested in mimicking the new European music than in hybridising it with other forms. In this respect, as he himself has pointed out, the oft-cited connection with groups such as Kraftwerk was no more than a starting point: "What I was passionate about in relation to Kraftwerk was their singular determination to stand apart from stereotypical American chord sequences and their wholehearted embrace of a European sensibility displayed through their music," David explained in 2001. "This was their very important influence on me." However, "Kraftwerk's approach to music had in itself little place in my scheme. Theirs was a controlled, robotic, extremely measured series of compositions, almost a parody of minimalism. One had the feeling that Florian and Ralf were completely in charge of their environment, and that their compositions were well prepared and honed before entering the studio. My work tended to expressionist mood pieces, the protagonist (myself) abandoning himself to the zeitgeist (a popular word at the time), with little or no control over his life. The music was spontaneous for the most part and created in the studio. In substance too, we were poles apart. Kraftwerk's percussion sound was produced electronically, rigid in tempo, unmoving. Ours was the mangled treatment of a powerfully emotive drummer, Dennis Davis. The tempo not only 'moved' but also was expressed in more than 'human' fashion. Kraftwerk supported that unyielding machine-like beat with all synthetic sound generating sources. We used an R&B band. Since Station To Station, the hybridisation of R&B and electronics had been a goal of mine."

"We were both thinking very cinematically about this, Brian Eno later recalled. "We were both thinking that each of these pieces that we were doing should be like a small film of some kind." The experimental techniques brought to the studio by Brian Eno included the use of the "Oblique Strategies" cards which he had developed in 1975 with Peter Schmidt. The cards would be turned over by musicians at random during recording to reveal instructions such as "Emphasise the flaws", "Fill every beat with something" or even "Use an unacceptable colour". The results were a staggering departure for Bowie; with Eno's encouragement, he was now subjecting the music itself to the kind of randomisation he had already visited on the lyrics of previous albums. "I would put down a piano part, say," David explained in 1993, "and then take the faders down so you could only hear the drums and [Eno] only knew what key it was in. Then he would come in and put an alternative piece in, not hearing my part...we would leapfrog with each other, each not hearing each other's parts, and then at the end of the day put each other's parts up and see what happened."

Carlos Alomar was initially suspicious of Bowie's new off-the-wall approach: "I fought it for a second," he told Radio 2's Golden Years, "but, respecting his curiosity and his innovativeness, I said, 'Well, let me try this, maybe something will come of it'. And I'll tell you one thing - it was the best of all that I've ever done with David Bowie. I love the trilogy more than anything else."

Lyrically, too, Bowie was moving beyond the cut-ups of previous albums into an entirely impressionistic, non-linear concept. Eno, he explained, "got me off narration, which I was so intolerably bored with...Brian really opened my ideas to the idea of processing, to the abstract of communication." In sharp contrast with the verbosity of Diamond Dogs or Young Americans, Low is a lyrically sparse album; six tracks are instrumentals embellished at most by pseudo-Gregorian chants, while the remainder has only brief, fragmentary, repetitive lyrics charting the introspective isolation of Bowie's healing process.

During the sessions, David had to go to Paris to attend a court hearing as part of his proceedings against Michael Lippman. While he was away, Eno continued working on the understanding that if David liked the result he could use it on Low. This, Eno explained to the NME, "meant I could work without any guilty conscience about wasting somebody else's time because if he hadn't wanted them I would have paid him for the studio time and used them on my own album. As it happened, I did a couple of things that I thought were very nice and he liked them a lot." One result was the basic framework of "Warszawa", which was jump-started by Tony Visconti's four-year-old son Delaney playing a three-note sequence on the studio piano. Delaney and his baby sister Jessica had been brought to the Chateau by Visconti's wife, the once and future Mary Hopkin, who was invited during her visit to add backing vocals to "Sound And Vision".

By all accounts the Chateau d'Hérouville sessions were traumatic, interrupted by an episode of food poisoning and a succession of unhappy scenes arising from Bowie's conflicts with Lippman and with Angela, who arrived at the studio to introduce David to her new boyfriend. Visconti later called the session "a horrible experience" compounded by a "really antagonistic" relationship with the studio staff, with whom David had a falling-out when it became clear that information was being leaked to the French music press. Adding to his woes were unwelcome visitors from beyond the grave: the Chateau's former inhabitants Frédéric Chopin and George Sand were reputed to haunt the master bedroom and, still victim to the kind of superstitions that had threatened to overwhelm him in Los Angeles, David gladly surrendered the room to a sceptical Brian Eno - who was promptly awoken in the small hours by a ghostly hand on his shoulder. But there were lighter moments too: Carlos Alomar recalls ending each evening watching videos of the BBC's new hit Fawlty Towers, and Visconti confirms that "despite the outside pressures, when Bowie, Eno and I were in the studio working at our peak, it was magic."

Most of the band were present for the first five days only, after which Eno, Alomar and Gardiner remained to play overdubs. By the time Bowie wrote and recorded the lyrics everybody but Visconti and the studio engineers had departed. David had initially suggested that the first fortnight's recordings should be treated as demos but, Visconti later recalled, "after the two weeks had gone I said, 'We have much more than demos here, why do we have to re-record all this lovely stuff?' So we listened back, and the lesson learnt from that is that we keep the machines running while we're creating and we do all the demos on 24-track, just in case." After years of differing approaches, it was the Low sessions that saw Bowie plumping for the three-phase studio methodology he still favours to this day: backing tracks first, followed later by guest overdubs and instrumental solos, followed finally (sometimes weeks or even, in the case of Lodger and Scary Monsters, months later) by the composition of lyrics and the taping of vocals. It was a process he had used as far back as The Man Who Sold The World, but from here on it became the established norm.

At the end of September, with most of the album already recorded, Bowie and Visconti left the Chateau in favour of the Hansa Studios in West Berlin (but not, contrary to popular belief, the Hansa By The Wall premises where Low would later be mixed and "Heroes" recorded). It was to prove a decisive step: despite Angela's attempts to coax David back to his tax-exile residence in Switzerland, Berlin would become his new adoptive home. After a short spell in the Hotel Gehrhus, he moved into a seven-room flat at 155 Hauptstrasse, an area of tattered nineteenth-century finery in the city's unfashionable Schoneberg district, which remained his base for the next two years. "It was the antithesis of Los Angeles," he later said. "The people in Berlin don't give a damn about your problems. They've got their own...I thought if I could survive in Berlin without being mollycoddled, then I had a chance of surviving." After years of living in the relentless glare of celebrity, David revelled in the anonymity Berlin offered. For the first time since early 1972, he had stopped dyeing his hair; he gave away his designer clothes and wore jeans and checked shirts. Disguised by a wispy moustache and a short back and sides administered by Tony Visconti, he rediscovered the joys of exploring a city on foot and by bicycle.

But Berlin was more than just a conveniently anonymous recharging station. It was the city of Fritz Lang, Christopher Isherwood and Bertolt Brecht, the adoptive homes of George Grosz, Marc Chagall and the Brucke group, the melting pot of European modernism that had informed Bowie's work from the very beginning. "We just dug the whole idea that this was Berlin," said Iggy Pop later. "This is a war-zone, this is no man's land." In a sense, Berlin was the very pattern of the post-apocalyptic urban landscape David had already envisaged in Ziggy Stardust and Diamond Dogs. As an arrested crossroads between East and West, and between past and future, 1970s Berlin was the ideal spiritual home for Bowie. He referred to the city as "the artistic and cultural gateway into Europe in the twenties", saying that "virtually anything important that happened in the arts happened there."

David had now been painting on and off for over a year - Tony Visconti recalls him sketching portraits of John Lennon in early 1975, and by the time of The Man Who Fell To Earth and Station To Station it had become his favourite pastime. Now, inspired by the city's cultural heritage and his encounters with its exotic demi-monde, he began painting in earnest. Berlin was home to all manner of minorities - artists, immigrants, punks, drag queens - who appealed to Bowie's affinity with outsiders. After his Berlin concert in April 1976, he had befriended Romy Haag, the most celebrated of the city's drag artists, who now became a semi-permanent fixture. His off-duty adventures in Berlin's art galleries, drag clubs and late-night drinking haunts provided the backdrop of the withdrawn, post-traumatic soundscapes of Low and "Heroes".

"The first side of Low was all about me, "Always Crashing In The Same Car" and all that self-pitying crap," explained David a year later, summing up the prevailing mood as "isn't it great to be on your own, let's just pull down the blinds and fuck 'em all." But he went on to explain that "side two was more an observation in musical terms: my reaction to seeing the East bloc, how West Berlin survives in the midst of it, which was something I couldn't express in words. Rather it required textures..."

Contrary to popular belief, however, Berlin's mythical "decadence" was not the quality which primarily attracted David to the city. "Berlin was my clinic," he said some years later. "It brought me back in touch with people. It got me back on the streets; not the street where everything is cold and there's drugs, but the streets where there were young, intelligent people trying to get along, and who were interested in more than how much money they were going to make a week on salary. Berliners are interested in how art means something on the streets, not just the galleries." In 1977 he declared that he had become "incapable of composing in Los Angeles, New York, London or Paris. There's something missing. Berlin has the strange ability to make you write only the important things. Anything else you don't mention, you remain silent, and write nothing...and in the end, you produce Low."

At Hansa Bowie completed the final tracks, "Weeping Wall" and "Art Decade", and added vocals to some of the Chateau recordings. The tail end of the sessions coincided with what was effectively the last gasp of David's marriage with Angela, who visited him in November 1976 to discuss their relationship. The stresses of recent times culminated in a dramatic incident on November 10th when David collapsed with a suspected heart attack and was rushed by Angela to the city's British military hospital. His condition was diagnosed rather less sensationally as an irregular heartbeat brought on by excessive drinking, and by the time the story broke Angela was back in London, appearing in a fund-raising revue called Krisis Kabaret with her boyfriend Roy Martin. The end came not long afterwards on another visit to Berlin when David refused Angela's demand that he fire Coco Schwab. "I went into Corinne's room," writes Angela in her biography, "gathered up her clothes and some of the gifts I'd given her in better times, threw them out of the window into the street, and called a cab and caught a flight to London." Angela and David met only once more to exchange legal documents, and their divorce became final in February 1980.

Low lives up to its name, offering in its few sparse lyrics a numbing parade of private neuroses, from the agoraphobic ("wait until the crowd goes", "pale blinds drawn all day") to the isolated ("sometimes you get so lonely", "you never leave your room") to the violent ("breaking glass in your room again", "always crashing in the same car") to the out-and-out nihilistic ("nothing to read, nothing to say"). Bowie's apprehension that the album might never be released was not without foundation. Horrified RCA executives expecting another Young Americans or Station To Station pulled the album from the Christmas 1976 schedule and, as David later recalled, one of them offered to buy him a house in Philadelphia "so he can write some more of that black music". Tony Defries, whose royalty settlement ensured that he retained a keen interest in David's commercial stock, did his best to stop Low being released at all.

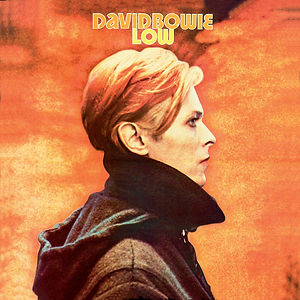

The conspicuously Eno-esque working title New Music: Night And Day remained in place until a very late stage in the album's development, even appearing on the interior labels of the cassette release prepared by RCA Canada, although this version was withdrawn before circulation. Low eventually appeared in January 1977, a week after David's thirtieth birthday, adorned with a heavily treated cover photograph from The Man Who Fell To Earth showing Bowie in profile. He later confirmed that the visual pun - "low profile" - was deliberate: not only was Low his least commercial album yet, but he did practically nothing to promote its release, preferring instead to tour as Iggy Pop's keyboard player. Only later did he speak of the album's "terribly important" position in his career, explaining in 1983 that Low offered "a world of relief, a world that I would like to be in. It glowed with a pure spirituality that hadn't been present in my music for some time. Mine had in fact almost become darkly obsessed...That album, more than any of the others that we did, was responsible for my cleaning up musically, and my driving for more positive turns of phrase, if you will, in my music. Except for a slight relapse in Scary Monsters." Similarly, in 2001 he remarked that "I get a sense of real optimism through the veils of despair from Low. I can hear myself really struggling to get well."

Low garnered mixed reviews from a truly baffled press. In Melody Maker Michael Watts hailed it as "a remarkable record and certainly, the most interesting Bowie has made. It's so thoroughly contemporary, less in its pessimism, perhaps, though that's deeply relevant to these times than in its musical concept: the logic of bringing together mainstream pop...and experimental music perfectly indicates what could be the popular art of the advanced society we are moving into." Cream's Simon Frith unexpectedly called the album "a fun record, such a refreshing jeu d'esprit...Low made me laugh a lot," while Billboard praised the "well defined, laid-out instrumental journeys into some brooding, mysterious lands."

Most critics, however, were united in their distaste. Another writer in Cream considered the record "inaccessible", while the Boston Phoenix dismissed it as "experiments in drone, repetition and time annulment". Long-time Bowiephile Charles Shaar Murray, reviewing the album very much in the shadow of punk, told NME readers that Low was "so negative it doesn't even contain emptiness", branding it "a totally passive psychosis, a scenario and soundtrack for total withdrawal...Futility and death-wish glorified, an elaborate embalming job for a suicide's grave...an act of purest hatred and destructiveness...it stinks of artfully counterfeited spiritual defeat and emptiness...comes to us at a bad time and doesn't help at all." Few albums have ever elicited such a savage response, and none has ever deserved it as little. The album confounded its detractors (whom Eno described as "bloody thick"), reaching number 2 in the UK chart and, perhaps even more impressively, number 11 in America. Despite the hostile reaction it received from many critics at the time, it is now widely regarded as one of the most brilliant and influential albums ever recorded.

Low was also a spectacularly clever record for Bowie to release at a time when rock journalism was obsessed with one group and one group only: The Sex Pistols. Punk offered nothing essentially new for Bowie, as anyone who has heard the live thrash-outs of The Spiders From Mars will testify. "When Ziggy Stardust fell from favour and lost all his money," David said at the time, "He had a son before he died, Johnny Rotten." Certainly, Bowie had patented Johnny Rotten's punk archetype on the sleeve photo of the re-released Space Oddity album four years earlier - flimsy jumper, dazed stare, dishevelled red hair, bad teeth and all. In his book Glam!, Barney Hoskyns presents a persuasive analysis of punk as "glam ripping itself apart", and more than one commentator has remarked on the obvious connection between glam's colourful aliases (Ziggy Stardust, Gary Glitter, Ariel Bender) and punk's (Sid Vicious, Rat Scabies, Polly Styrene). Wisely for a 30-year-old riding the wave of a new generation, Bowie left punk well alone: by sidestepping it he avoided becoming either a fogey or a father-figure. In any case, David's hermetic isolation throughout much of 1976 and 1977 meant that punk was all but finished by the time he encountered it: "Whether it was my befuddled brain or because of the lack of impact of the English variety of punk in the US, the whole movement was virtually over by the time it lodged itself in my awareness," he admitted many years later. "Completely passed me by. The few punk bands that I saw in Berlin struck me as being sort of post-1969 Iggy, and it seemed like he's already done that."

The contribution of experimental prog guitarist Ricky Gardiner, once described by Visconti as Low's "unsung hero", has often been underestimated, but it is the album's swathes of electronic sound, trailblazing percussion effects and deadpan, emotionally burned-out vocals that demand the attention. They were not merely the touchstone for up-and-coming acts like Gary Numan, but a major influence on talents from such diverse ends of the spectrum as Joy Division, Soft Cell, Depeche Mode and Trevor Horn. As Bowie later said, "the position we adopted on Low coloured what was to happen in English music for some time...[especially] in terms of ambience and drum sounds. That 'mash' drum sound, that depressive gorilla effect, set down the studio drum fever fad for the next few years." Speaking of the so-called "triptych" of Low, "Heroes" and Lodger in 2001, he added: "For whatever reason, for whatever confluence of circumstances, Tony, Brian and I created a powerful, anguished, sometimes euphoric language of sounds. In some ways, sadly, they really captured, unlike anything else in that time, a sense of yearning for a future that we all knew would never come to pass. It is some of the best work that the three of us have ever done. Nothing else sounded like those albums. Nothing else came close. If I never made another album it really wouldn't matter now, my complete being is within those three. They are my DNA."

Although Brian Eno receives only one co-writing credit on Low and plays on just six of the eleven tracks, he has been given increasing credit over the years by revisionists, including Bowie himself. When Philip Glass reworked sections of the music as the "Low" Symphony in 1992, the credit was to "the music of David Bowie and Brian Eno". Glass himself has hailed the original album as "a work of genius", and he is not alone in his opinion. Few participants in modern music can fail to be touched, enthralled and irrevocably influenced by Low. Most Bowie fans consider it one of the pinnacles of his career.